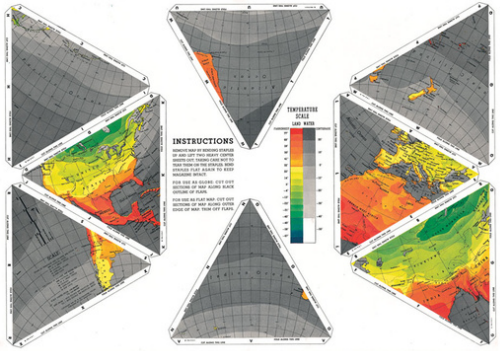

First published as an article in The March 1st 1943 edition of Life magazine, Buckminster Fuller’s compromise projection contains far less distortion than other flat maps. The map was printed as a pull-out section designed to allow readers to assemble the map. It divides the globe’s surface into a continuous surface without bisecting major land masses and it is unique in that there is no right way up. It can be read from any orientation and rearranged in a number of alternative ways.

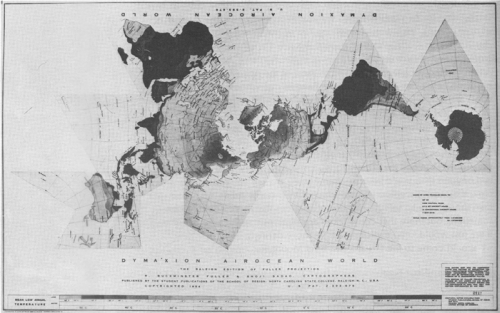

Fuller went on to publish his ‘Airocean’ world map using the projection in 1954 that employed a modified icosahedron. The term Dymaxion was a name applied by Fuller to this and many other of his inventions. Each triangular edge matches the scale of a partial great circle on the corresponding globe and it that sense, points within each facet shrink towards its middle point (which is the inverse of many other projections).

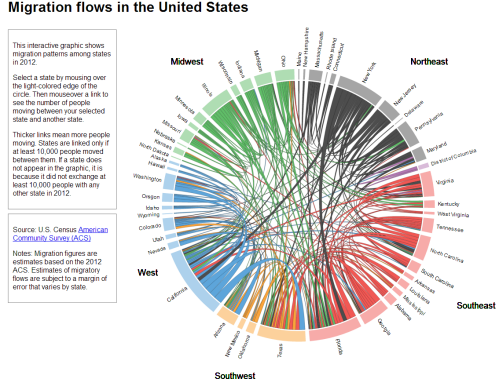

The map was intended to be folded in different ways though in its most common orientation it shows an archipelago of almost uninterrupted continents and allows the plotting of migratory paths and flow particularly well.

The original Life magazine article can be read here.