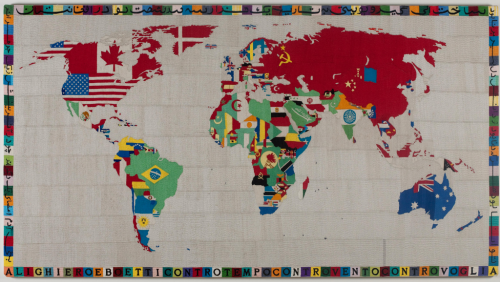

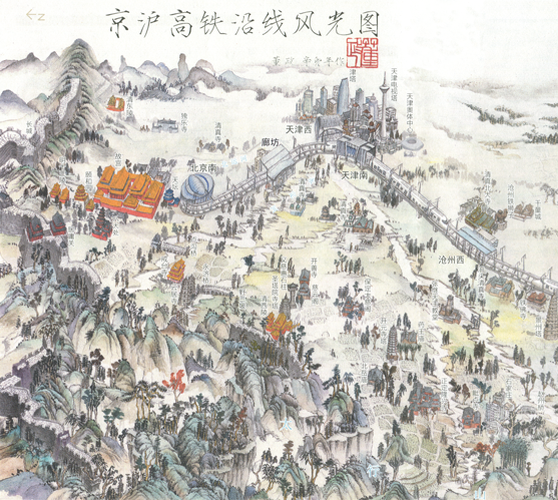

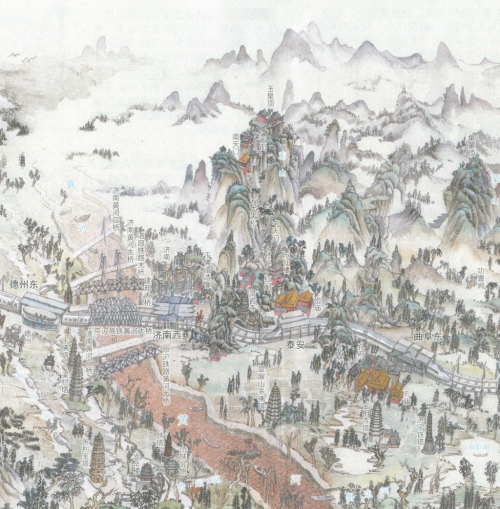

Cartography has always been, in part, an artistic pursuit and in a world where many more maps are now made digitally we see a lot of bland cartography in design terms. Still, hand drawn maps inspire and have something very human about them. The marks of the pen and the shades of the colouring give the map character. Of course, when we’re growing up we routinely draw with pen and paper and the recent entries to the International Cartographic Association’s Barbara Petchenik children’s map competition evidence the imagination and artistry among the world’s youngsters.

This beautiful map from 15 year old Liao Zhi Yuan of China typifies not only a high level of artistry but also in interpretation and use of the map form. Pictorial maps often make heavy use of non-map imagery or combine elements to make up a map form. Here, the use of the aquatic lotus flower, reflecting cultural significance, forms the shape of the landmasses of the world map within an ornamental pond. It’s a simple yet effective idea that communicates a message of harmony using established symbolic visual metaphors. The map itself is a lovely piece of cartographic art and well drawn.

Of course, we don’t all have to have an artistic talent to make maps but if you’re going to make maps like these it certainly helps. It should also act more generally as an inspiration to think creatively and to aspire to make maps that are set apart from the rest.