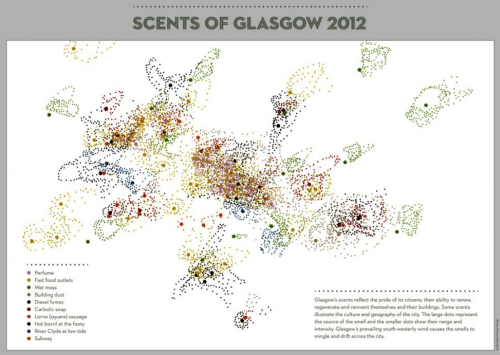

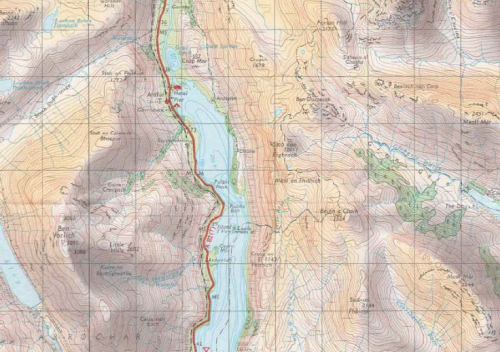

Forgive the posting of one’s own work but as it’s the author’s birthdays on 8th and 10th Feb and the map won the ‘best map at the International Cartographic Conference in Dresden, 2013 we figured if others feel it has cartographic merit it’s deserving of inclusion in MapCarte…

This map was designed in two ways for both print and web, each allowing the consideration of the opportunities and limitations of the two mediums. With print, you get the map at once and it has an immediate impact yet we have to resort to an inset for the detailed areas. With the web, multiscale allows us to increase detail as we zoom in and so we can use a hex-binning technique at smaller scales and switch to true locations for every location at larger scales. We can also switch out the basemap at larger scales online to use a satellite image that gives us a clearer impression of the actual character of the landscape. Additionally, whereas we can only include c.20 text vignettes describing the incidents on the print map, the full details of all 700+ incidents can be explored on the web map.

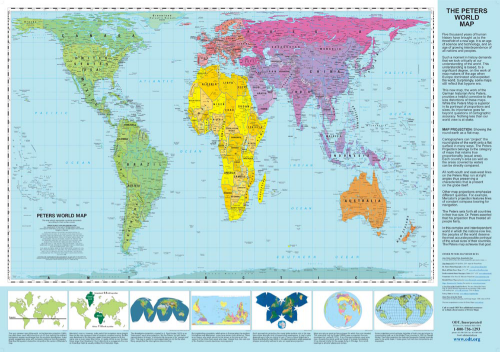

The map employs a chromastereoscopic technique that allows us to encode some variable using spectral colours. When viewed through chromadepth glasses (that contain small prisms) red is refracted so it appears closer to the eye and blue refracted so it appears farthest away. Other colours are refracted between these two endpoints which creates a 3D holographic effect. Elevation was encoded in this way so we see deep red plateaus descending to the blue of the Colorado. Other map elements used pure red hues to build subtle visual hierarchies for the map content. The ‘comic book’ style complements the dramatic colours and theme and pictograms are used to represent categories of incident..as ‘warning’ triangles on the print map and tesselated hexagons on the online version.

The chromasteroscopic technique is unlike other 3D techniques in that the map is perfectly legible without the 3D glasses…a little jarring visually because of the highly saturated colours but Grand Canyon provided a great landscape to map this way because of the naturally red rock.

Print map can be downloaded here.

Online version of the map is here.

Chromadepth glasses can be obtained from American Paper optics here

Thanks for the indulgence…normal service resumes tomorrow.