Fantasy maps are increasing in number and scope as more video games take place in imagined worlds and computer power is able to render environments in ever more detail. The world of Minecraft is particularly interesting from a cartographic perspective since users can add worlds. Indeed, Ordnance Survey have added their Minecraft version of Great Britain to the virtual world. More details here.

But imaginary maps, or maps of imaginary worlds, are not new. Take, for example, The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings trilogy by J. R. R. Tolkien. The films of the last decade have brought a new found interest that has seen countless maps and other geo-products developed including the very well produced The Hobbit Journey Through Middle-Earth as a way of teasing the film The Desolation of Smaug. You can see the web map here which uses a mix of sound, visuals and purported satellite imagery and maps that even have dancing clouds. It’s a great example of the current trend for photo-realistic worlds and immersive, interactive content.

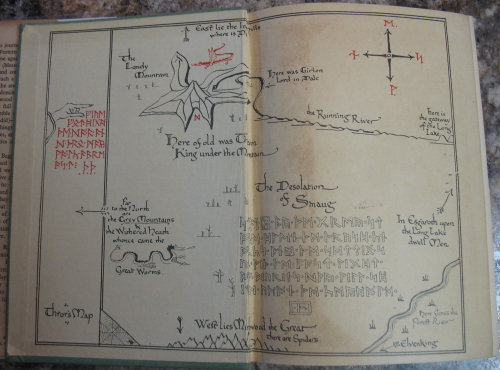

Here though, we want to reflect on a much simpler yet more important and cartographically intersting version – the originals drawn by J. R. R. Tolkien himself.

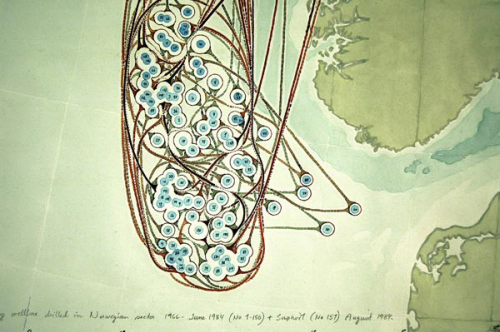

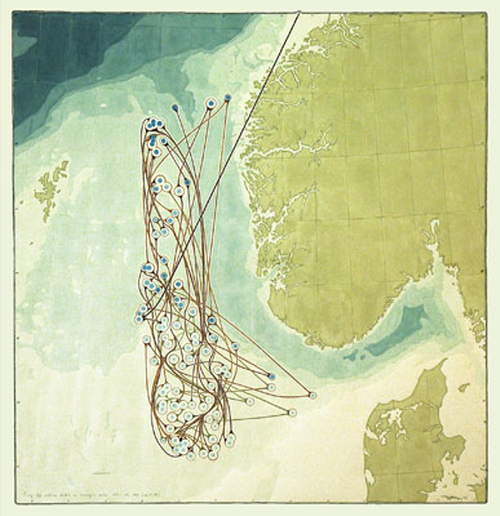

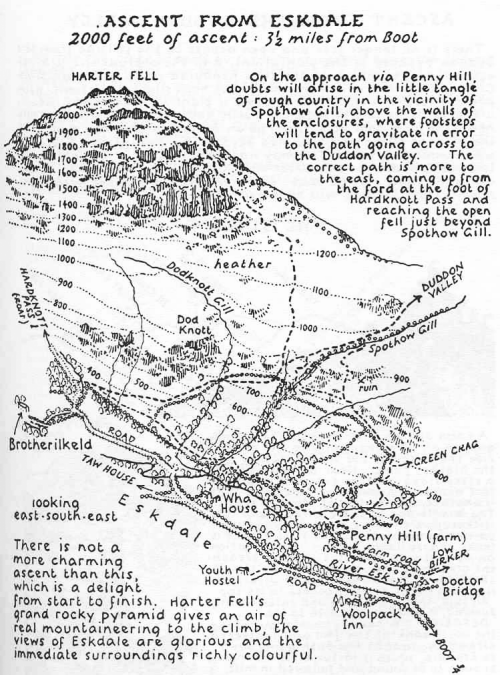

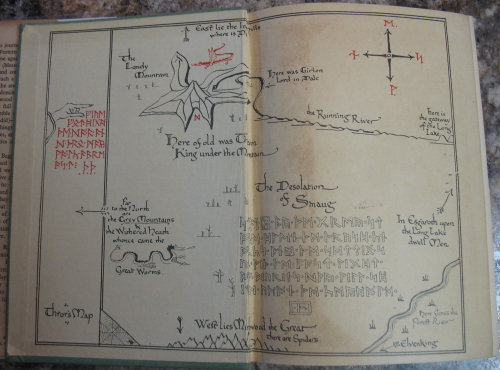

The lead map in this entry and the one above come from the inside front and back covers of The Hobbit published in 1937. They are two colour prints of the world as Tolkein envisaged it without CGI or fancy special effects. It presents the layout of the world with the key places. Mountains are represented in aspect across an otherwise planimetric map though there’s a hint at perspective with far off mountainscapes appearing on the horizon. It’s a sort of progressive projection and Tolkien was clearly a student of cartography enough to replenish his maps with high quality cartographic flourishes.

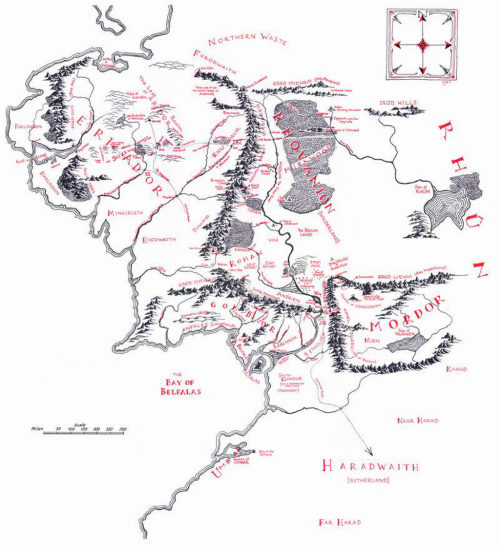

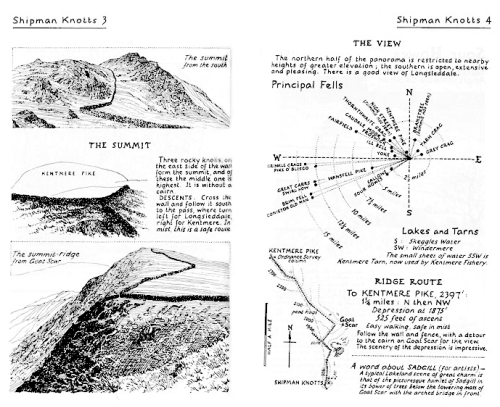

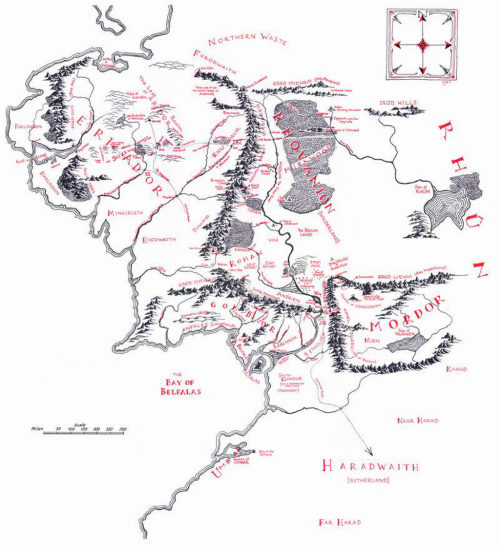

The final map here is from The Lord of the Rings book The Fellowship of the Ring, published in 1954 and gives us a view of the larger world the characters inhabit. Again, the two colour approach is used which allows highlights to be generated and contrast achieved. The linework is simple but effective and the use of white space hints at a world beyond.

The final map here is from The Lord of the Rings book The Fellowship of the Ring, published in 1954 and gives us a view of the larger world the characters inhabit. Again, the two colour approach is used which allows highlights to be generated and contrast achieved. The linework is simple but effective and the use of white space hints at a world beyond.

As an inspiration for the landscapes that eventually made it to Peter Jackson’s films it’s easy to see how these original maps inspired the use of the landscape of New Zealand. A great example of the use of the real world to act as a set for an imaginary one.

Beautifully simple maps that bring to life an imagined place and which, along with others, underpin the fantasy maps of today.