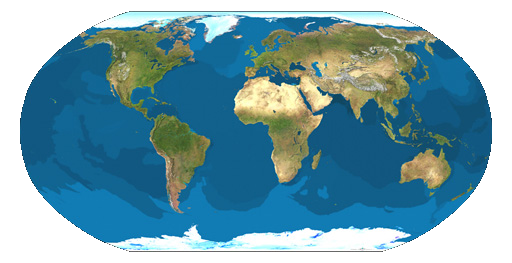

What better to represent the culmination of cartographic knowledge and achievement at the close of the twentieth century than a portrait of the Earth from space?

What better to represent the culmination of cartographic knowledge and achievement at the close of the twentieth century than a portrait of the Earth from space?

The first cloud-free, high-resolution composite image of the Earth was completed on 15th April 1990. It featured on the title page of the National Geographic World Atlas that year and was produced by artist Tom Van Sant with technical assistance from Lloyd Van Warren, Leo Blume and James Knighton. Using multiple whole-Earth mosaics collected by Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) sensors on board TIROS-N (Television and InfraRed Observation Satellite Next generation) satellites, the composite was derived from over 2,000 images with a ground resolution of 4.6 km. The project required ten months of software development and both interactive and non-interactive methods of creating the mosaics using a Stardent GS1000 Graphics Supercomputer – then amongst the most powerful machines of its type.

But is it a map? ‘First-of-a-kind portrait from space’ was its title in the November 1990 issue of National Geographic, strengthening the cartographic pedigree of this latest mapping achievement. A portrait is usually intended to flatter its subject; while appearances need to be accurate to form a resemblance, complete faithfulness – even allowing for Oliver Cromwell’s desire for ‘warts and all’ – is beyond the objective of the artist. Hence, as a map, Van Sant’s Earth portrait aptly represents the blend of art and science that characterises cartography and its drive for an aesthetic perfection that reflects impossibility more than reality. Not only do we see a cloud-free and perfectly and evenly illuminated Earth, but one in perpetual bloom with maximum vegetation cover wherever you look. Drainage and relief were enhanced using high-resolution hydrology and elevation databases and the images themselves were filtered, corrected and manipulated to produce the best view possible.

But is it a map? ‘First-of-a-kind portrait from space’ was its title in the November 1990 issue of National Geographic, strengthening the cartographic pedigree of this latest mapping achievement. A portrait is usually intended to flatter its subject; while appearances need to be accurate to form a resemblance, complete faithfulness – even allowing for Oliver Cromwell’s desire for ‘warts and all’ – is beyond the objective of the artist. Hence, as a map, Van Sant’s Earth portrait aptly represents the blend of art and science that characterises cartography and its drive for an aesthetic perfection that reflects impossibility more than reality. Not only do we see a cloud-free and perfectly and evenly illuminated Earth, but one in perpetual bloom with maximum vegetation cover wherever you look. Drainage and relief were enhanced using high-resolution hydrology and elevation databases and the images themselves were filtered, corrected and manipulated to produce the best view possible.

In The Power of Maps (1992), Denis Wood deconstructs Van Sant’s Satellite Map of Earth, unveiling the very human forces behind each decision in its production. Yet, aptly completed on the birthday of Leonardo da Vinci, the image is also a reminder of cartography’s unique fusion of art, science and technology – and the cartographer’s desire to portray a pleasing world.