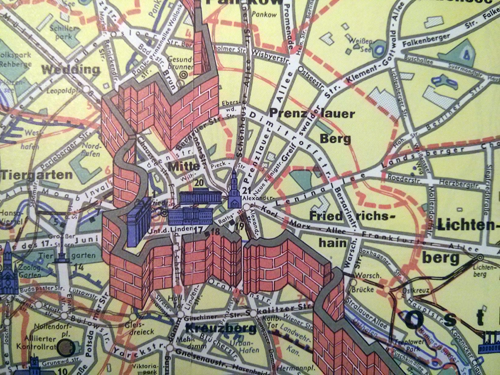

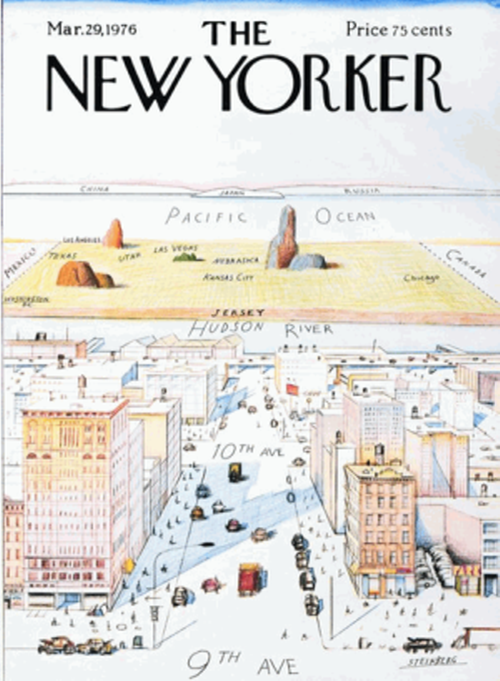

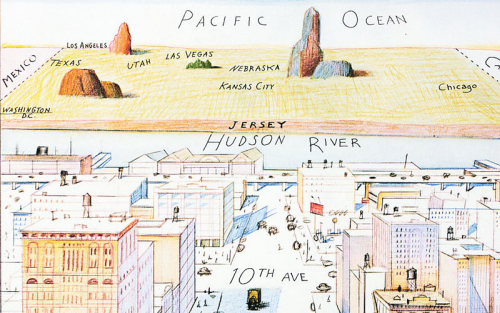

Maps have always been used as propagandist or persuasive documents. People’s implicit trust of a map works in favour of the map maker who may have a particular message to communicate either blatantly or subliminally. During times of conflict it’s also common to see maps used for political gain or to exaggerate either a threat or a relative success in battle to illustrate the threat or to garner support for the cause. The Cold War was no different and maps were produced by all parties that attempted to illustrate a situation to their benefit. Here, a map of Berlin that illustrates the wall, constructed in 1961, might be seen as showing the street network and various features but you don’t have to dig very far to see how the design supports the message.

Maps have always been used as propagandist or persuasive documents. People’s implicit trust of a map works in favour of the map maker who may have a particular message to communicate either blatantly or subliminally. During times of conflict it’s also common to see maps used for political gain or to exaggerate either a threat or a relative success in battle to illustrate the threat or to garner support for the cause. The Cold War was no different and maps were produced by all parties that attempted to illustrate a situation to their benefit. Here, a map of Berlin that illustrates the wall, constructed in 1961, might be seen as showing the street network and various features but you don’t have to dig very far to see how the design supports the message.

It’s an illustrative map which in it’s own right brings a rather abstract aesthetic to the map which perhaps downplays the real situation. The map shapes the reality of the city with the main element, the wall itself, shown as a dominant wall of red brick slicing its way through the city. The map is planimetric yet the wall is isometric to emphasise it rising from the city, its very height being used to emphasise its function as a barrier. Gates are shown as narrow slices through the wall and in the western part of the map, barbed wire is shown as a further discouragement to anyone who may even think of attempting to get from east to west. Barbed wire encloses the edge of the Western part of the map to make clear the message.

The western side is populated with considerable detail whereas the east has very little features and few labels being marked simply as Area IV – East Berlin (which was the Soviet sector). Even the subway lines which are illustrated in detail in the west and which run through the east are shown with stations that are noted as ‘out of service’. The reality was somewhat different – you were not allowed to embark or alight at the stations. There’s even a sense of colour being used as part of the aesthetic with the map border being shown in the flag colours of black, yellow and red.

The western side is populated with considerable detail whereas the east has very little features and few labels being marked simply as Area IV – East Berlin (which was the Soviet sector). Even the subway lines which are illustrated in detail in the west and which run through the east are shown with stations that are noted as ‘out of service’. The reality was somewhat different – you were not allowed to embark or alight at the stations. There’s even a sense of colour being used as part of the aesthetic with the map border being shown in the flag colours of black, yellow and red.

Of course, this map only tells one side of the story but shows how design can be used to support a particular message. Maps exist that were made for use in East Berlin that showed merely an empty space in the West – a clear message that there was nothing but a void and no particular reason to seek an escape.

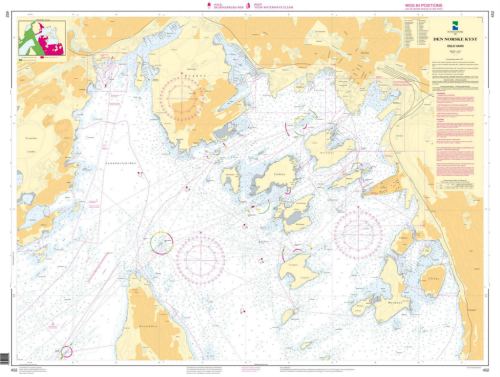

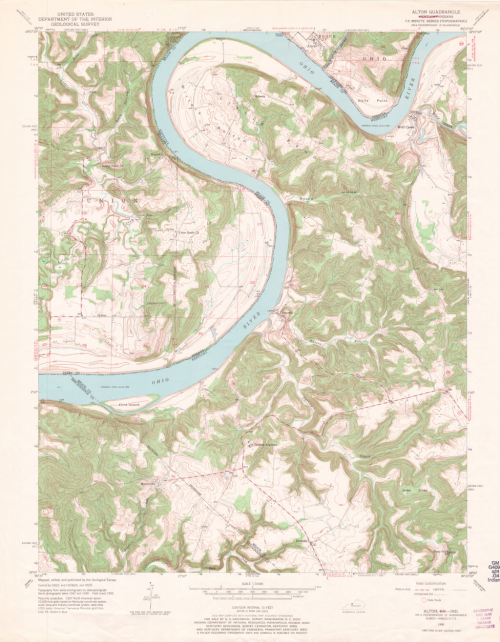

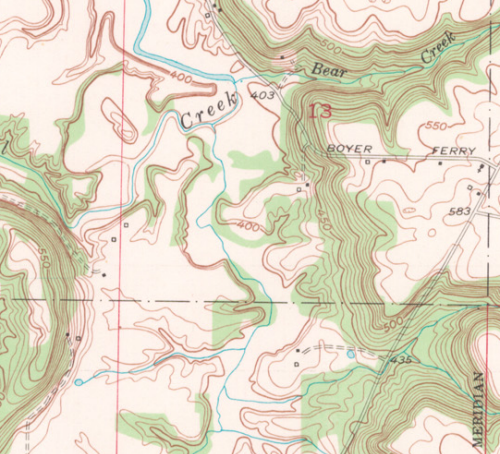

As a brand, the series is instantly recognizable and successful. The content serves both civilian and military purposes and supports varied usage. Marginalia is well structured and complex information delivered in a succinct, well organised manner. The series was officially completed in 1992 and while The National Map (

As a brand, the series is instantly recognizable and successful. The content serves both civilian and military purposes and supports varied usage. Marginalia is well structured and complex information delivered in a succinct, well organised manner. The series was officially completed in 1992 and while The National Map (