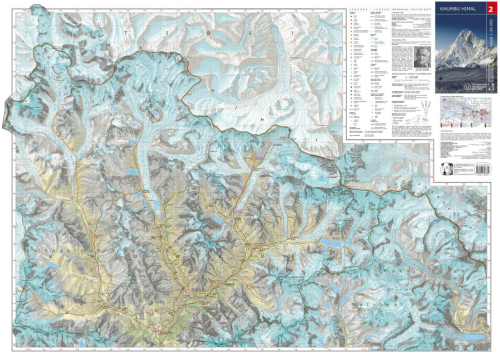

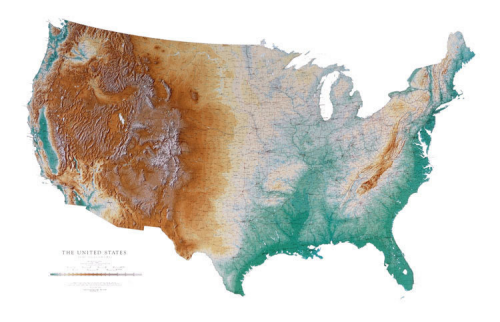

Relief representation is always a challenge for cartographers. It often makes or breaks a map giving the representation realism or appearing to sit uncomfortably. The choice of method alone is cause for a headache…illuminated relief shading, hachures, contours, hypsometric tinting and a multitude of alternative approaches provide a rich palette. The ultimate goal is to create a representation that mimics the three-dimensional character of the landscape itself and which can be easily understood by the map reader. Unless you know how to read a map, traditional techniques such as contours can appear confusing despite them being blatantly obvious to the map-maker. Here then, is perhaps the most readily understood form of relief representation – the plastic relief model.

Relief representation is always a challenge for cartographers. It often makes or breaks a map giving the representation realism or appearing to sit uncomfortably. The choice of method alone is cause for a headache…illuminated relief shading, hachures, contours, hypsometric tinting and a multitude of alternative approaches provide a rich palette. The ultimate goal is to create a representation that mimics the three-dimensional character of the landscape itself and which can be easily understood by the map reader. Unless you know how to read a map, traditional techniques such as contours can appear confusing despite them being blatantly obvious to the map-maker. Here then, is perhaps the most readily understood form of relief representation – the plastic relief model.

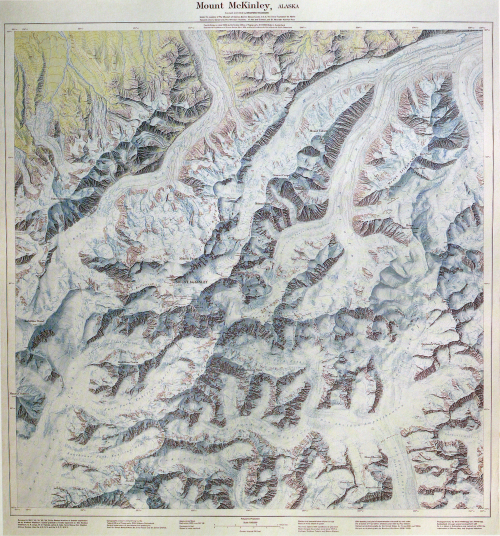

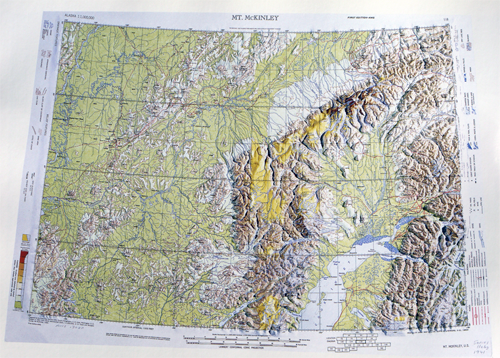

This example of Mount McKinley illustrates the pinnacle of small format plastic relief model design. The model itself is well produced. The two dimensional surface is created in a mould that warps the plastic using heat. The physical character of the landscape, its hills, valleys, ridges and depressions are faithfully reproduced and once the topographic map has been overprinted the landscape springs to life in real 3D. Of course there are problems with this sort of map. Firstly, they often require considerable vertical exaggeration to make features across a large area appear sufficiently to make the third dimension believable. Exaggeration, of course, is part of the cartographer’s generalization toolbox and applied with care can emphasise the features sensibly which this example evidences.

The Lambert conical projection gives this map its curvature but the cartographers have used the flat borders to great effect to relay the detail for the legend. Rather than orientating everything to read in the same way, the reader has to rotate the model to see different information. A nice touch that promotes the idea that the model can and should be viewed from multiple angles to reveal different perspectives. The printed map is of a high quality that helps ensure the model is pleasing to the eye as well as detailed and informative.

The main drawback to the adoption of plastic relief models is their relatively high cost of production, storage issues and the fact that the plastic degrades. Maps such as these remain collectible and sought after. They have also been used as a way of generating two-deimensional shaded relief using a camera with a long focal length and then combining the photograph with other planimetric detail. The use of LiDAR scanners have also been used to create three-dimensional point cloud of plastic relief models to allow the recreation of a computerised 3D model.

Nothing compares to the use of a three-dimensional object to show relief. It provides a tactile representation of reality that no computer generated model can similarly achieve. This is a beautiful example of the type and as a delightful map object in its own right. Of course, a 2D computer screen cannot do this work justice but…go find a copy!