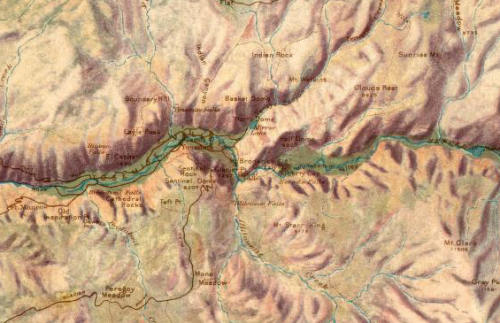

As more and more maps are created by digital means it’s easy to forget that many digital techniques still fail to achieve the artistry that a hand drawn map can bring to bear. Cartography has always been heavily populated by artists who have brought considerable graphical skill to the process of design and production but as we search for ever more automated techniques that more people can deploy we perhaps lose a little of that exceptional individual work. Hand drawn maps bring a style that can be as different and unique as a Monet to a Van Gogh or a Turner to a Banksy.

Here, John Renshawe shows us a rich palette of colour with deep browns and earth tones to depict Yosemite Valley. Lush greens and bright blues complement this excellent colour scheme that attempts to show the landscape as rich as one might find it in reality.

The manually developed hill shade is particularly striking and though analytical hillshades have advanced tremendously, the ability of an artist to consider individual elements in the terrain rather than a computer’s approach of applying a technique systematically provides a unique and pleasing result.

The manually developed hill shade is particularly striking and though analytical hillshades have advanced tremendously, the ability of an artist to consider individual elements in the terrain rather than a computer’s approach of applying a technique systematically provides a unique and pleasing result.

The text sits comfortably in the map and the use of a border in a complementary colour completes the overall image. A beautiful, rich and warm map.