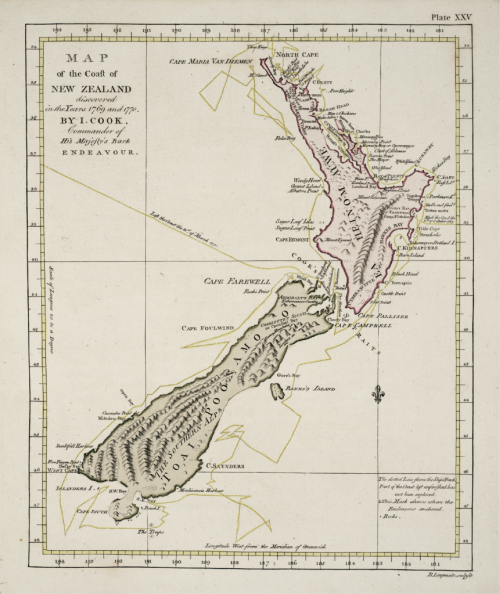

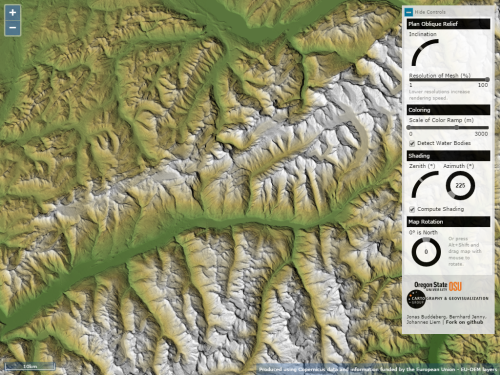

Imagine sailing to the southern oceans in the late 1700s without a proper clock and no accurate way of navigating and then attempting to create a map of the coastline of a country that had never been circumnavigated before. Captain James Cook was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the Royal Navy. After making detailed maps of Newfoundland during previous expeditions to the Pacific, Cook set out on his ship, Endeavor, to map uncharted territories.

Cook mapped New Zealand in 1769/70 in greater detail and on a scale not previously achieved. He both surveyed and named features, and recorded islands and coastlines on European maps for the first time. His mastery of surveying and cartography matched his seamanship in adverse conditions and his map of New Zealand is a masterful example of cartography given the conditions in which he was working. Indeed, It wasn’t until his second and third Pacific voyages in the 1770’s that he took one of Harrison’s clocks with him so his ability to make a map of this quality without a proper way to establish longitude was impressive.

In design terms the map is a simplified representation of the surveyed landscape. The outline of New Zealand is almost unbelievably accurate and the internal topography shows mountainscapes with molehill representations typical of the period. Labels are well positioned but its the coastline that is the main achievement of representation here. Accuracy is he success story of this map though it is a beautiful document and an important historical document.