Maps have incredible power to affect the way we perceive and feel about a place before, during, and after we experience it. Cartography really can change the way we see the world.

Maps have incredible power to affect the way we perceive and feel about a place before, during, and after we experience it. Cartography really can change the way we see the world.

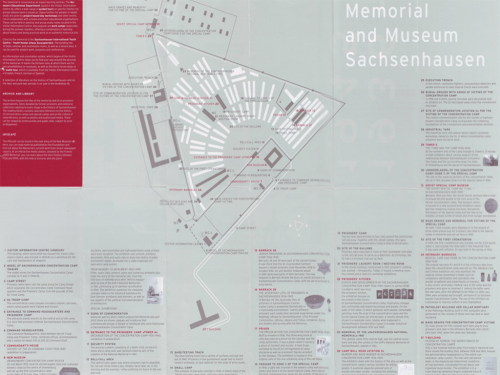

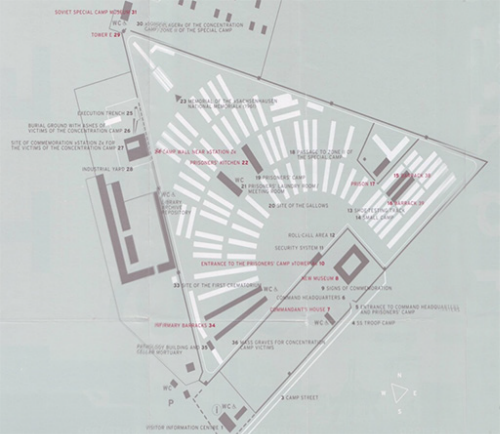

Located 22 miles (35 km) north of Berlin, the concentration camp complex at Sachsenhausen was designed and regarded by the SS (Schutzstaffel) as ‘ideal’. The infamous words ‘Arbeit macht frei’ (Work makes [you] free) are incorporated within its gates, through which 200,000 political prisoners – and eventually those regarded as ‘racially or biologically inferior’ – passed from 1936 to 1945. Sachsenhausen subsequently became a Soviet ‘Special Camp’, housing 60,000 inmates until 1950 and, after several years of neglect, was transformed into the Sachsenhausen National Memorial in 1961. Following the reunification of Germany, the site became the state-funded Sachsenhausen Memorial and Museum in 1993 and today attracts around 400,000 visitors each year.

At first, the map itself may seem nothing special. But its power lies in its subtlety and simplicity, through its poignant and eerily clinical blend of dark red, greys and white. The map presents us with a cold, soulless landscape and invokes an attitude fit for entering a place that has borne witness to countless atrocities and felt the depths of human cruelty and systematic murder. We are not to regard this as any normal landscape; neither beautiful nor commodified, but barren and scarred.

At first, the map itself may seem nothing special. But its power lies in its subtlety and simplicity, through its poignant and eerily clinical blend of dark red, greys and white. The map presents us with a cold, soulless landscape and invokes an attitude fit for entering a place that has borne witness to countless atrocities and felt the depths of human cruelty and systematic murder. We are not to regard this as any normal landscape; neither beautiful nor commodified, but barren and scarred.

The map therefore captures the uniquely strong sense of place with a perfectly muted aesthetic that aligns our expectations, encourages reverence, and in doing so re-educates our understanding of the expressive range of cartographic language.