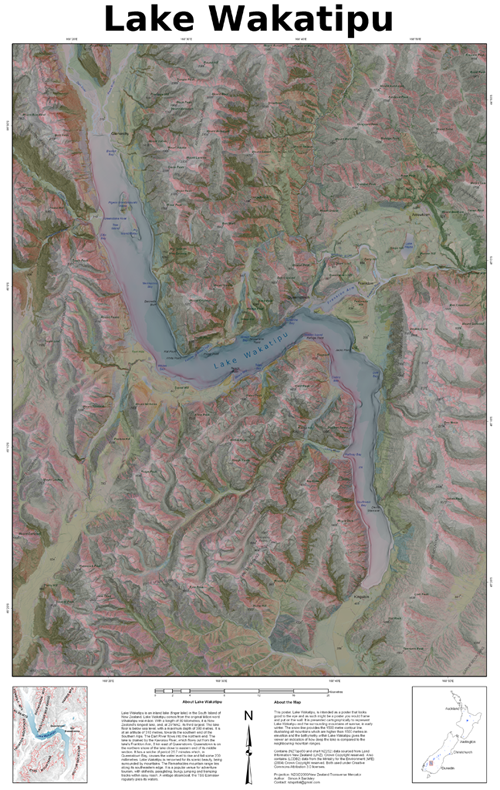

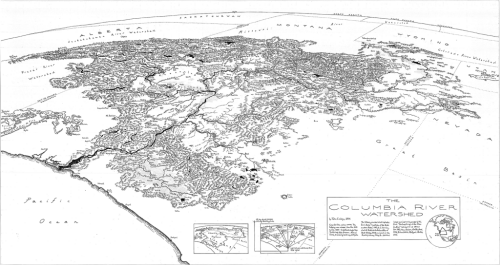

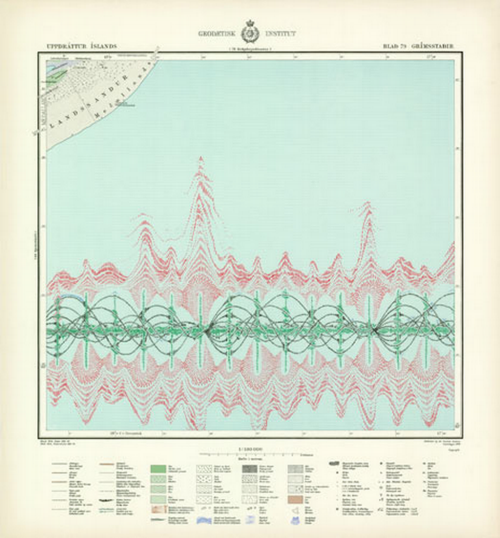

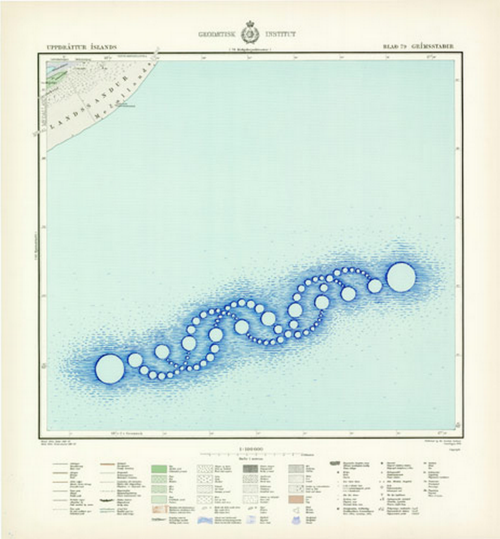

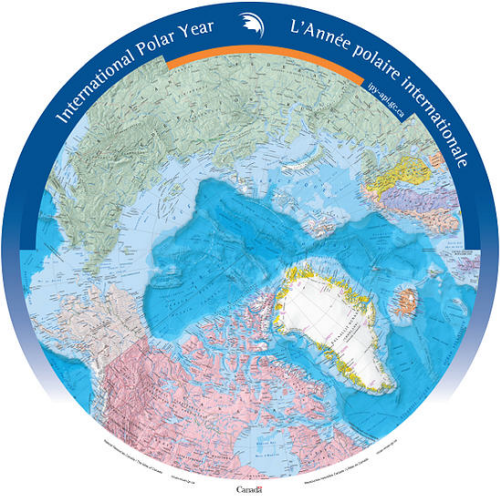

Fitting a map to a piece of paper or a screen is not necessarily the optimum approach to creating a suitable layout. While creating maps of different shapes on a screen is technologically a step too far, when the map is designed for print there remains the opportunity to play with projections and shapes. Here, the Atlas of Canada Program and NRCam illustrate how to handle the shape of a map perfectly. Mapping the North CIrcumpolar region, the region north of 55 degrees latitude, demands an azimuthal projection. Consequently, the map is round rather than the more usual equirectangular maps we tend to see.

Fitting a map to a piece of paper or a screen is not necessarily the optimum approach to creating a suitable layout. While creating maps of different shapes on a screen is technologically a step too far, when the map is designed for print there remains the opportunity to play with projections and shapes. Here, the Atlas of Canada Program and NRCam illustrate how to handle the shape of a map perfectly. Mapping the North CIrcumpolar region, the region north of 55 degrees latitude, demands an azimuthal projection. Consequently, the map is round rather than the more usual equirectangular maps we tend to see.

The map illustrates national boundaries, Canada’s 200 mile exclusive economic zone as well as the usual toporaphic and reference detail one would associate with a small scale map. The scale of 1:10,400,000 results in a map 1.6 metres in diameter and the impact of such a large map is impressive. Visually, the circular shape immediately invites exploration. Upon closer inspection the drawbacks of a circular shape have been mastered. Typographic placement is a particular difficulty. Horizontal text dowsn’t work on a circular map but ensuring curved text follows an appropriate line is imperative to create harmony. Sometimes type is placed across a curve relating o the landscape but often it follows either lines of longitude as they radiate or lines of latitude when the meridians become too steep up and down the page.

Colour is well handled, further detail of minimum permanent sea ice extent, the tree line and historical surveyed locations of the Magnetic North Pole from 1831 to 2007 are included to make the map a combination of topographic reference and thematic map. It’s a successful hybrid.

The unconventional format makes perfect sense for the map but brings with it an interesting added dimension that creates interest and reinforces the information portrayed.

The original map (square format) can be downloaded from Natural Resources Canada with additional information here.