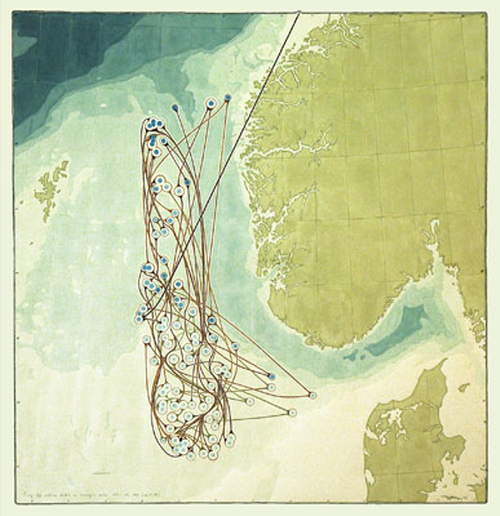

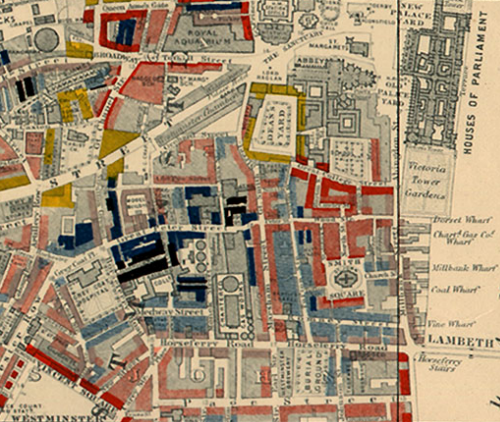

Often the simplest and most abstract maps are the most eye-catching and when the map is designed to appear in a magazine article that’s precisely what’s needed. This is a very simple dataset of wine consumption per person by country. There isn’t much one can do with the data if you’re constrained to a standard world boundary dataset. You could use a choropleth or a proportional symbol map or perhaps venture into cartogram territory but if you have the artistic license to explore different approaches then you can develop something totally different.

Often the simplest and most abstract maps are the most eye-catching and when the map is designed to appear in a magazine article that’s precisely what’s needed. This is a very simple dataset of wine consumption per person by country. There isn’t much one can do with the data if you’re constrained to a standard world boundary dataset. You could use a choropleth or a proportional symbol map or perhaps venture into cartogram territory but if you have the artistic license to explore different approaches then you can develop something totally different.

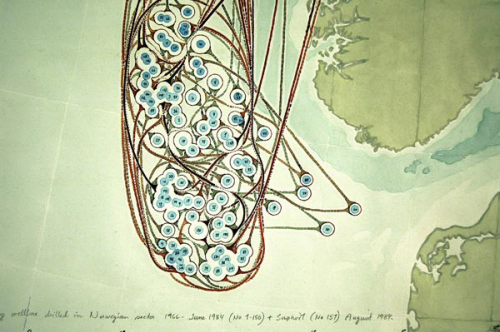

This, then, is really just a set of proportional circles rearranged in the form of a bunch of grapes. One might class it as a Dorling cartograpm though there isn’t really any sense of geography being maintained. The colours work well and even though colour is not used to encode anything about the data the different colours don’t detract from the message. This proves that cartographic rules can be broken if a separate element in the design is strong enough to carry it. Normlly, we’d associate different the different hues to some qualitative difference between countries but instead, the grapes motif overrules that impression. It does so effectively.

The overlaps also add to the effect even though usually we’d avoid overlaying symbols like this using transparency as it can confuse the message. Because the colour is not part of the map’s encoding the author can get away with it. Finally, the leaves, the ornate lettered cartouche and the simple legend complete this elegant and effective map.