Maps fight a good war. Geographic intelligence has always been a pre-requisite for battle, whether in the form of Ezekiel’s clay model of Jerusalem or a digital terrain model from a reconnaissance drone.

Maps fight a good war. Geographic intelligence has always been a pre-requisite for battle, whether in the form of Ezekiel’s clay model of Jerusalem or a digital terrain model from a reconnaissance drone.

The year 2014 marks one hundred years since the outbreak of World War I, a global conflict which began on 28th July 1914 and ended on 11th November 1918 with a cost of 16 million lives and the downfall of four Empires in continental Europe. After the German army had invaded neutral Belgium and Luxembourg, their march on Paris was halted and what became the Western Front fell into a battle of attrition with a line of trenches that changed little until 1917.

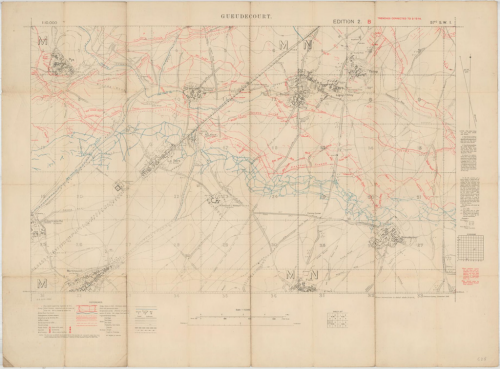

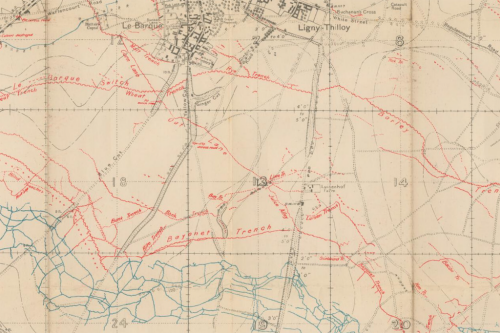

When the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) crossed the English Channel in August 1914, it relied upon on existing maps at 1:40,000 (Belgium) or 1:80,000 (France) and some at smaller scales, which were useful for planning troop movements, but not for the largely static war of attrition that required a more detailed knowledge of enemy defensive positions. From early 1915 the Geographical Section of the General Staff (GSGS) at the War Office began to produce new, larger-scale maps for the fighting units at the Front. At a scale of 1:10,000, the new maps could reveal details of the enemy Front Line, machine gun posts, bunkers, communication trenches to the rear and any defensive positions. Small teams of Royal Engineers and Ordnance Survey surveyors gradually grew into larger field survey companies who could correct, print and distribute maps from the British lines.

The Battle of the Somme, fought by the British and French forces against Germany from 1st July to 18th November 1916, was one of the largest battles of the war and claimed over one million casualties. The 1:10,000 sheet shown here, Gueudecourt, depicts the trenches as on 2nd December 1916, with German positions in red and British/French in blue (as was the standard until these colours were reversed in early 1918). Gueudecourt was one of the most distant objectives of the British during the Battle of the Somme. The village saw decisive action from the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, who played a key role in capturing and successfully defending a German strong point. A memorial near the village, comprising a bronze caribou standing atop a cairn of Newfoundland granite, commemorates their achievement and sacrifice.

The Battle of the Somme, fought by the British and French forces against Germany from 1st July to 18th November 1916, was one of the largest battles of the war and claimed over one million casualties. The 1:10,000 sheet shown here, Gueudecourt, depicts the trenches as on 2nd December 1916, with German positions in red and British/French in blue (as was the standard until these colours were reversed in early 1918). Gueudecourt was one of the most distant objectives of the British during the Battle of the Somme. The village saw decisive action from the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, who played a key role in capturing and successfully defending a German strong point. A memorial near the village, comprising a bronze caribou standing atop a cairn of Newfoundland granite, commemorates their achievement and sacrifice.

Images by permission of the National Library of Scotland