Taking world shapes, maps, outlines or other map-related content gives artists a palette to work from that immediately creates recognition in the audience. People are instantly able to recognise the shapes of countries so the barrier to seeing and becoming interested in a piece of abstract art is perhaps lessened. Brigitte Williams has created numerous works that follow this principle and in so doing she organises her work in some sense of structure to provide a commentary on the relationship between the patterns she makes and out understanding of the world.

Taking world shapes, maps, outlines or other map-related content gives artists a palette to work from that immediately creates recognition in the audience. People are instantly able to recognise the shapes of countries so the barrier to seeing and becoming interested in a piece of abstract art is perhaps lessened. Brigitte Williams has created numerous works that follow this principle and in so doing she organises her work in some sense of structure to provide a commentary on the relationship between the patterns she makes and out understanding of the world.

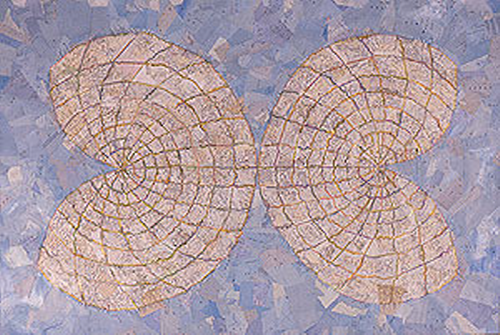

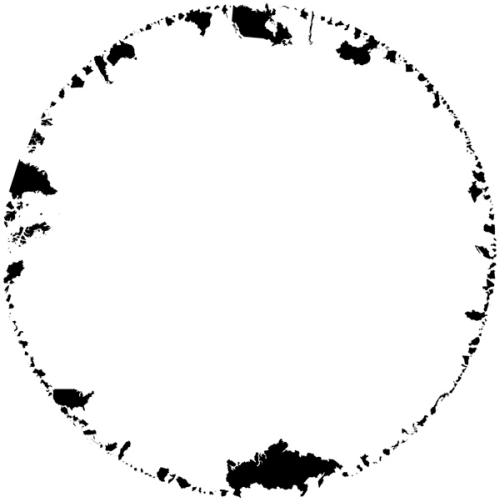

In Peace is a stark, circular image that is predominantly white space yet has the shapes of countries form a circle. A circle of peace perhaps? The white emptiness in the middle perhaps also suggestive of a lack of communication or maybe some other visual metaphor? It’s a strong aesthetic.

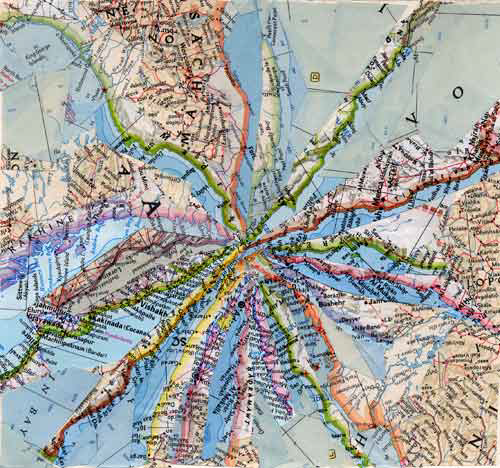

A second piece, called Dislocation, shatters the perfect circle and positions the countries in an apparent random order. They are actually placed quite deliberately and seem to have perfect borders and an amount of white space dissecting them.

A second piece, called Dislocation, shatters the perfect circle and positions the countries in an apparent random order. They are actually placed quite deliberately and seem to have perfect borders and an amount of white space dissecting them.

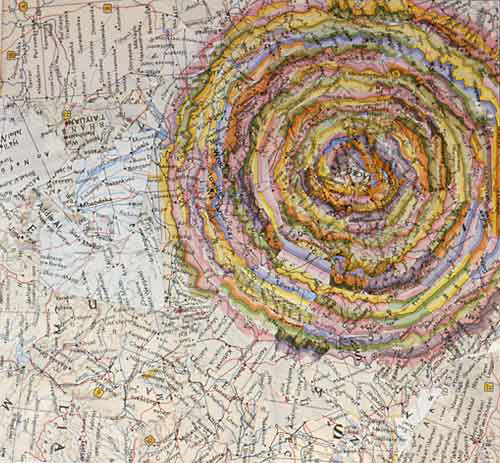

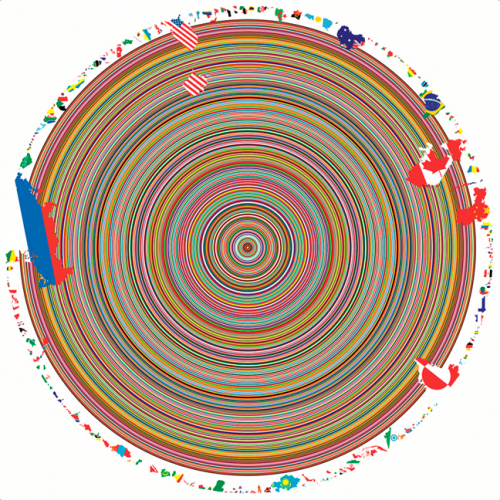

Finally, she also uses colour and splashes the countries shapes with flags which seep into a series of concentric rings to create an almost hypnotic pattern. This work is called United.

Finally, she also uses colour and splashes the countries shapes with flags which seep into a series of concentric rings to create an almost hypnotic pattern. This work is called United.

Williams is simply borrowing shapes from the world of mapping and repurposing them but creating new works that make us reflect on the structure of our world and place within is no bad thing. Sometimes the very familiar shape and structure of our world on a standard globe becomes rather unremarkable and it’s important to stand back and reflect on different perspectives once in a while.

You can see more of Willaims’ work here.