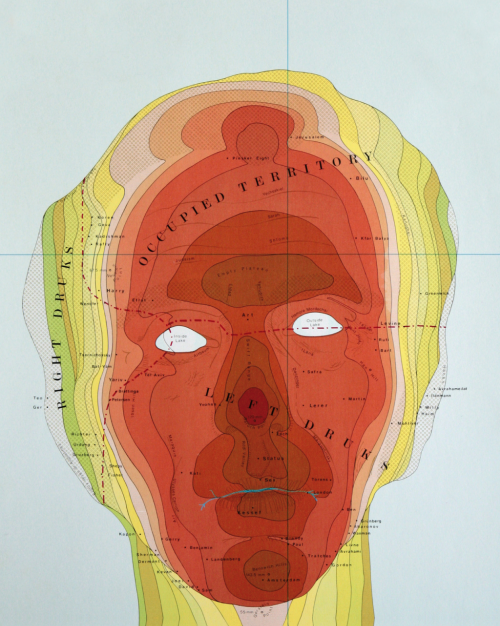

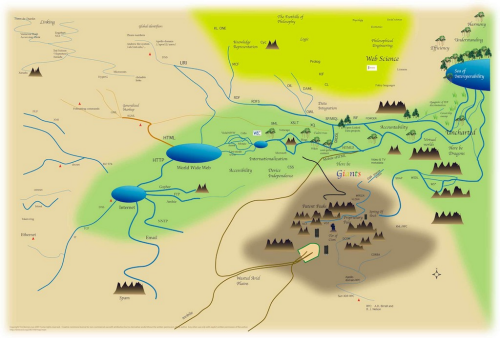

If I say that this map by Sir Tim Berners-Lee will never win any design awards then you’d be perfectly within your rights to question why it warrants a spot in MapCarte. That would be to ignore the map’s function which is to explain how the world wide web works to mere mortals…and the use of a map is a perfect metaphor. The complex world of wires that Berners-Lee is credited with inventing during his time at CERN. Of course, the world has grown way beyond those early beginnings and is far more complex with a range of complementary technologies which interlink in weird and wonderful ways.

If I say that this map by Sir Tim Berners-Lee will never win any design awards then you’d be perfectly within your rights to question why it warrants a spot in MapCarte. That would be to ignore the map’s function which is to explain how the world wide web works to mere mortals…and the use of a map is a perfect metaphor. The complex world of wires that Berners-Lee is credited with inventing during his time at CERN. Of course, the world has grown way beyond those early beginnings and is far more complex with a range of complementary technologies which interlink in weird and wonderful ways.

The map, then, portrays these relationships and shows how various components connect together and what each is used for. Even if you have no idea what TCP is or how Google fits into the scheme of things this map gives you a sense that you can at least position them within. There are some wonderful touches and the map isn’t devoid of graphical treats. Google isn’t directly mentioned but the colour coding of the word ‘Giants’ is unmistakable and riffs off the logo. There’s also some vague areas thrown in that refer to accountability or logic or efficiency and understanding. There’s even a ‘here be dragons’ reference.

So what of the map’s overall appearance? Well it’s reflective of an early computer game aesthetic. It’s simple and clearly generated using simple paint tools. In many ways it works in this form where a more accomplished map or diagram might not. It reflects complexity through simple graphics. There’s no place to hide in this realm as depicted and the seas and mountains add to the sense of some sort of fantasy map, perhaps almost Tolkien-esque. Even the fonts used perhaps add to the impression that this is a role-playing game map. It’s a look and feel that works well.