This series of great maps tends to focus on a single map, its design and success. OpenStreetMap is fundamentally different but equally deserving of inclusion. It isn’t a map as such but the main output is data – map data that anyone can use freely to create their own maps and support their own endeavors. The idea of making a free, open and editable mappable dataset and the movement it has inspired has revolutionised mapping and was very much by design.

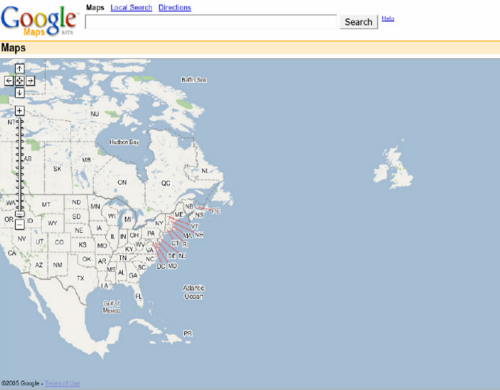

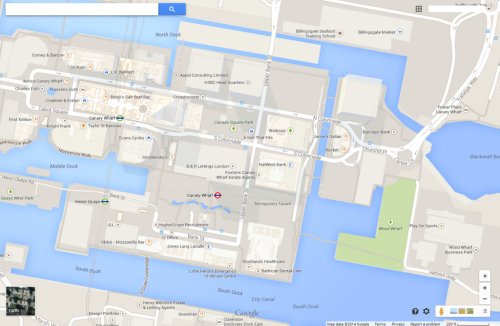

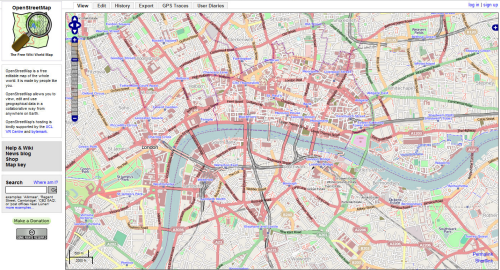

At the time of its creation, the United Kingdom in particular was both one of the most detailed and accurately mapped places on earth yet, paradoxically, most of the data was kept locked behind the paywalls of proprietary and national mapping organisations. Inspired, Steve Coast set about creating the phenomenon that is OpenStreetMap by focusing first on the UK itself. Volunteers using GPS receivers undertook ground surveys and collected data which was uploaded and used to populate the first iteration of the map. The idea, and crucially the process of contributing data, was simple. Users collected data using GPS receivers and made notes then uploaded the points of interest and tracklogs to the OpenStreetMap web site (www.openstreetmap.org). They could categorise and attribute the data into a consistent schema and edit data submitted by others directly in the browser to improve accuracy and detail. The community driven map was born.

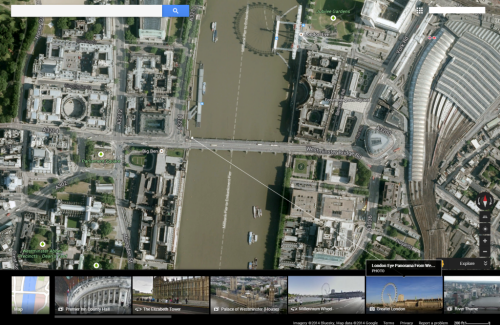

Since its inception, the ways that people can add data have increased including the ability to use aerial photography as a backdrop for data creation (in effect, on-screen digitising). Many other commercial organisations have also allowed the use of their data either directly or as an intermediary step to populate OpenStreetMap.

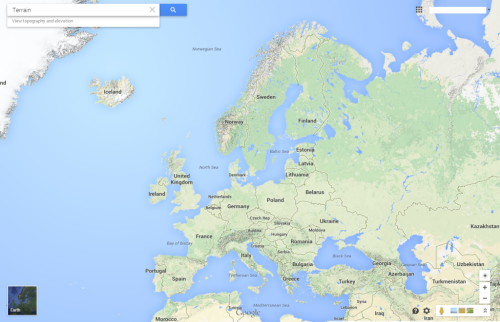

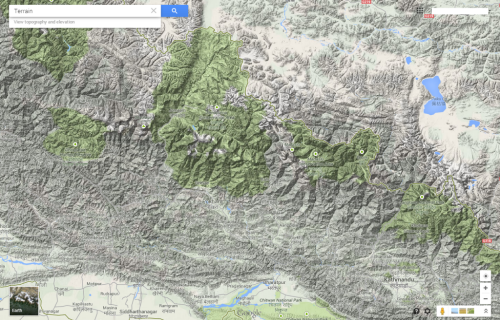

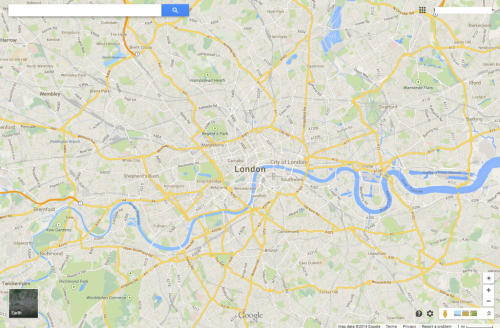

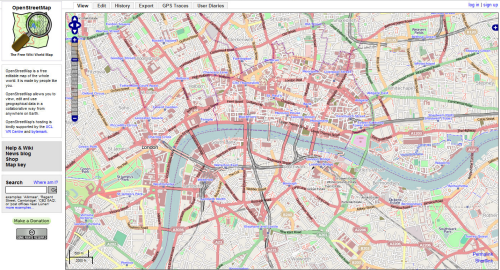

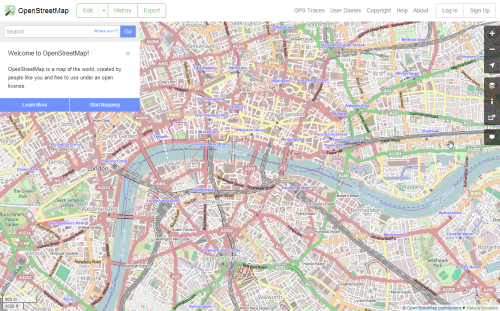

Click image to go to the current OpenStreetMap web site

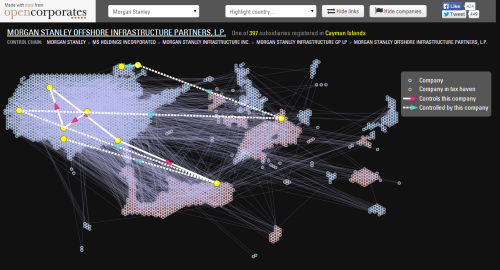

Early adopters were mainly those in countries that had relatively poor access to open map data. United States contributors were initially conspicuous by their absence mainly due to the relatively rich and available data they already enjoyed. Contributors are varied culturally, geographically and technically. This, coupled with uneven data coverage, has led to some criticism of the accuracy and consistency of the dataset but in early 2013 the number of registered contributors reached 1 million and growth and data quality continue to improve. Maps can be used directly in the browser or the data can be processed using a number of methods and used in other applications. It is this flexibility and ability to use the data under, formally, a Creative Commons (CC) license and now an Open Database License (ODbL) that has led to its wide uptake. OpenStreetMap is used in many commercial applications but perhaps most importantly it has been critical in the disaster management and response of major natural disasters. For example, volunteers responding to the 2010 Haiti earthquake mapped roads, buildings and refugee camps of Port-au-Prince in just two days. As a way to generate rapid data for crisis mapping and to support disaster response and recovery efforts it’s hard to see a better approach than that which OpenStreetMap supports.

A piece of great design in its own right, ItoWorld’s 2008 animation showed the phenomenal growth of OpenStreetMap edits. Similar examples illustrate the mapping of disaster response.

OSM 2008: A Year of Edits from ItoWorld

ItoWorld’s visualisation paints a fascinating picture as the OpenStreetMap movement captures and publishes new features from single roads to entire countries. The simple temporal legend gives a sense of the speed at which data was acquired and reflects the impact and speed of OpenStreetMap itself in this era of democratized mapping and citizen science.

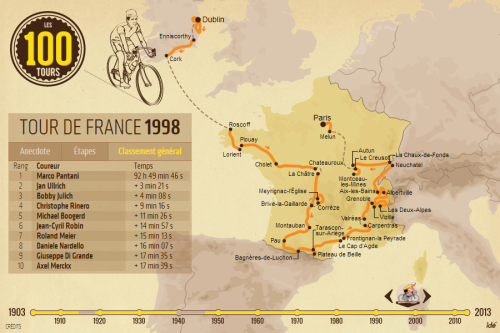

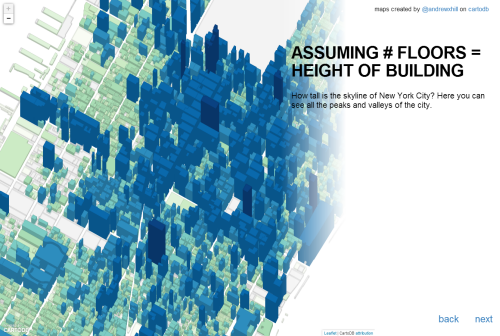

An impressive momentum has built amongst the community resulting in more people making and editing the data, making maps from the data, producing new and better software tools for the data and generating new and exciting products. Much of the use has been from non-geographers and non-cartographers which represents a massive departure from those more usually interested in maps. This burgeoning growth has certainly led to massive and often disruptive innovation some of which is truly innovative yet you’re more likely to see a terribly designed map made with OpenStreetMap data than you are a good one. This is in many ways inevitable as far more people who have non-geo backgrounds become users of OpenStreetMap data. That balance will shift as more people come to recognise not only the value of such a resource, but how to see it as more than just a technical challenge and use it effectively in tandem with knowledge and understanding of cartography. As for affecting the way map data is made available, OpenStreetMap has changed the landscape in profound ways. The freeing up of even the most tightly controlled geographical datasets is a work in progress but one from which there is no return.