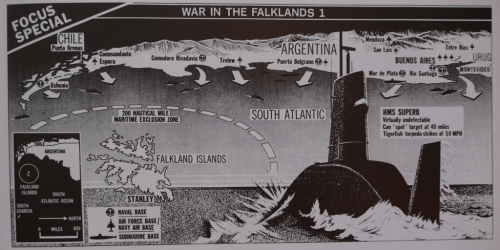

There’s nothing like conflict to get the cartographic juices of newspaper, magazine and television media flowing. It almost seems to ignite a battle to present the most compelling map or information graphic; one that brings together as much useful information in one dramatic illustration. The art in this is to ensure that clarity remains and to avoid the temptation to over-dramatise or place too much on the map. This is a challenge for cartography generally, but for a map that accompanies a newspaper article which is there as a supporting component to the story, the requirement to be prudent is paramount. The map needs to attract the reader to spend a few moments. It is a complement to the report. It doesn’t need to tell the whole story but it needs to contain the essential facts.

This French example from early in the first Gulf War shows how the balance can be achieved. there’s a tremendous amount of detail yet it’s illustrated in a clear, unimpeded fashion. The tilted block diagram is almost apologetic as the shape of Iraq is laid out amongst simple shapes of water bodies and mountains. But it’s the firepower from above that the article is emphasising as layers of armoury, missiles and satellite technology pour over the landscape. Scale is irrelevant. This is about showing the blanket capabilities of the allies. The illustration of bombs dropping through a clean-cut hole in the sky and those fired from the warship in the gulf itself are clinical. The laser-red of the satellite monitoring gives us a sense of precision. Of course, war is anything but clinical, clean and precise but these sort of illustrations present us with a sanitised version that explains the technology being used.

The maps used in such graphics are merely the canvas upon which a story is told but they are the crucial element. Combined with high quality illustrations, media maps do a good job of putting maps in front of many thousands of people.