Mapping physical space is the cornerstone of cartography but it certainly isn’t limited to that realm. In some ways, many of our own mental maps are the most interesting yet they are rarely drawn. We hardly ever see a physical representation of the way in which our brain sees the world with all its distortions based on familiarity and bias and how we get from A to B using our own unique points of reference. Of course, the realm of mental maps is a fascinating area of cartographic discourse in its own right but there are simpler ways of exploring how we think and feel about a place.

Mapping physical space is the cornerstone of cartography but it certainly isn’t limited to that realm. In some ways, many of our own mental maps are the most interesting yet they are rarely drawn. We hardly ever see a physical representation of the way in which our brain sees the world with all its distortions based on familiarity and bias and how we get from A to B using our own unique points of reference. Of course, the realm of mental maps is a fascinating area of cartographic discourse in its own right but there are simpler ways of exploring how we think and feel about a place.

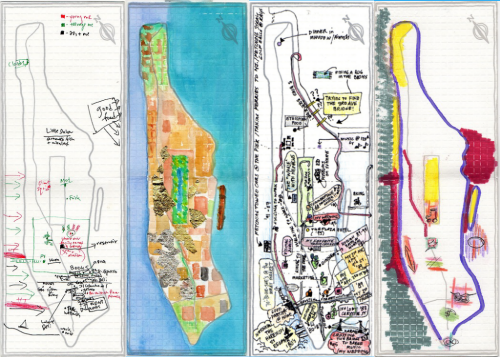

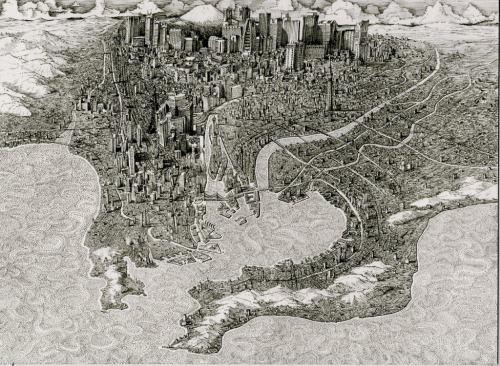

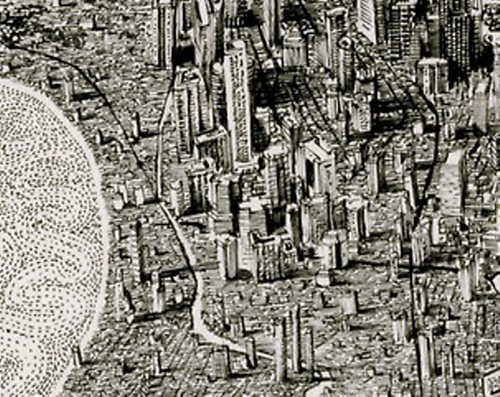

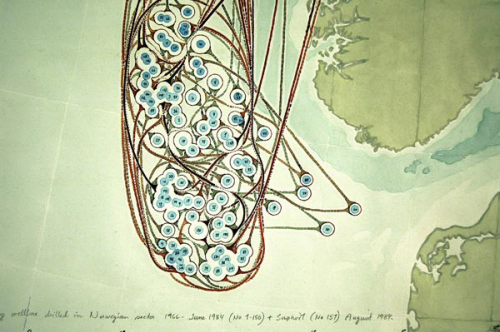

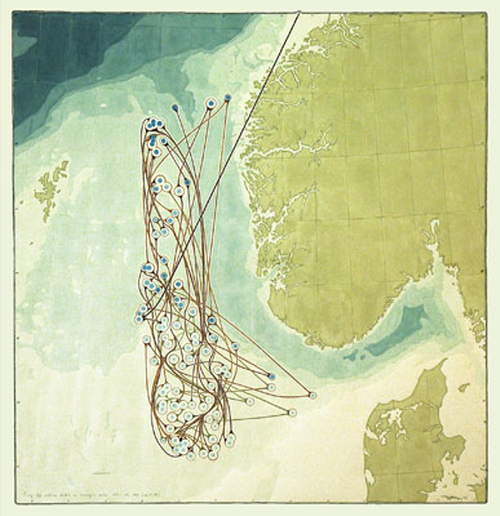

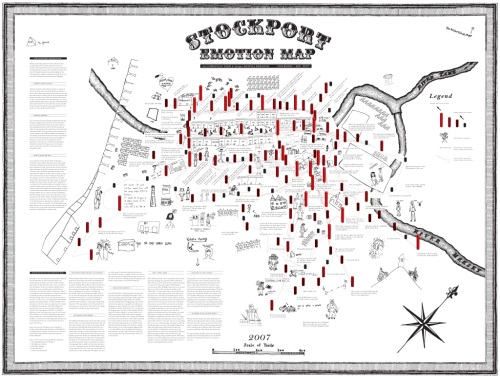

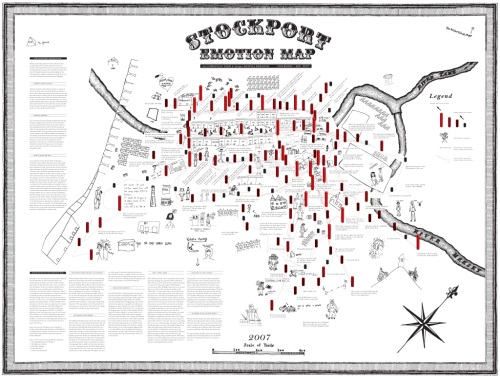

Christian Nold’s emotion map of Stockport in the UK goes beyond the conventional depiction of the buildings and urban fabric of a place. He has created a map that represents feelings, emotions, opinions and desires of local people. He bases the map on a project involving 200 people who completed a range of mapping exercises that required them to draw their responses to a variety of stimuli. What do they enjoy about Stockport? Where do they meet friends? Who are the most important or dangerous people in town? The resulting drawings were scanned and compiled into the map itself. He also measured individual arousal (positive or negative) at different places in town and included vertical bar graphs on the map to show how people react to different places. Finally, he annotated the measures with participant comments so we get a sense of what people think. It’s not one mental map – it’s a collective mental map.

What he ultimately creates is part art project, part insight into the way we really view a familiar place. The formation of clusters of concerns and comments gives rise to a way of seeing our surroundings that is often overlooked. These disconnected conversations become apparent through the map and reveal an until now hidden side to the way in which people feel about Stockport. For instance, the map revealed that the town’s history is somewhat marginalised, there is a predominance of shopping activities and young people feel somewhat isolated due to lack of provision of things they find interesting.

The map itself is a collage of different people’s work but that messy, unstructured appearance relates well to the project’s objective. This isn’t about creating a coherently designed view of features, it’s about exploring differences and the expression of those differences. The map won’t win any awards for the most beautiful map you’ve ever seen but it represents perhaps a hidden aesthetic – one that is only revealed when you stitch together seemingly random, disparate pieces into a whole. It’s not without graphical merit though – the hand-drawn approach follows through to Nold’s marginalia, borders and scale bar. There’s a consistent black on white treatment except for the emotional graphs that use colour effectively. Given the amount of random elements from multiple pieces, crafting a map that shows any amount of consistency in design is an achievement in itself.

Visit Nold’s web site here to see a larger version of the map and more detail. Nold has also taken completely different approaches to mapping different cities. Worth a look.

The 75 maps in the collection are published as a book and are truly fantastic as give us an insight into people’s personal worlds. The book very cutely includes a blank map at the back which invites readers to create their own map.

The 75 maps in the collection are published as a book and are truly fantastic as give us an insight into people’s personal worlds. The book very cutely includes a blank map at the back which invites readers to create their own map.