There’s a saying about things that are old become new again and we see plenty of that in cartography. In fact, many cartographic techniques seem to come in and out of fashion regularly as new map-makers find the technique or try and work out ways of creating a particular map type using new software. A good example recently has been the use of tesselated hexagons as a container for summarizing another dataset. We might call it hex-binning and for the last few years it’s become a popular way of mapping thematic point data because it creates visually and cognitively equivalent areas and which overcomes the death by push-pin red dot fever mapping.

There’s a saying about things that are old become new again and we see plenty of that in cartography. In fact, many cartographic techniques seem to come in and out of fashion regularly as new map-makers find the technique or try and work out ways of creating a particular map type using new software. A good example recently has been the use of tesselated hexagons as a container for summarizing another dataset. We might call it hex-binning and for the last few years it’s become a popular way of mapping thematic point data because it creates visually and cognitively equivalent areas and which overcomes the death by push-pin red dot fever mapping.

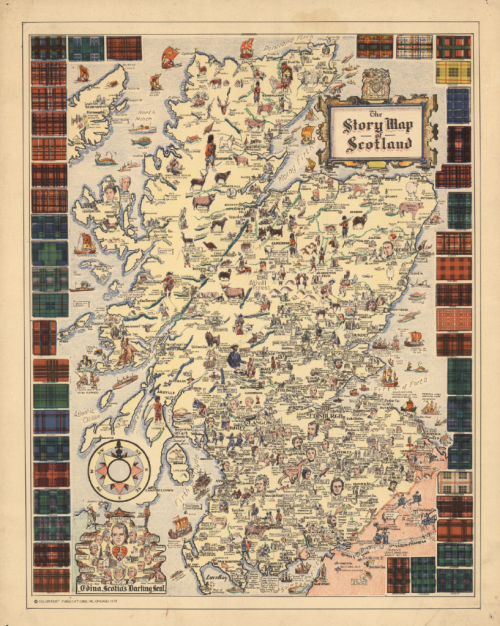

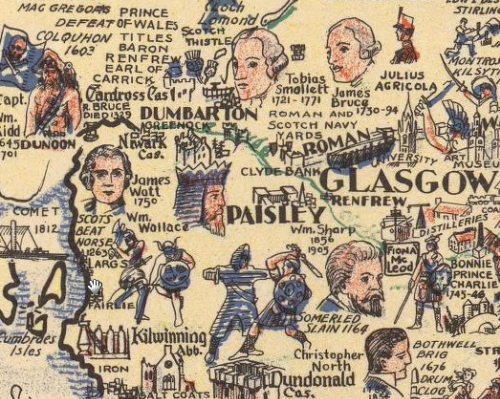

Another trend has been the use of new terminology to describe a particular type of map. To some of us a little older in the tooth a map is a map. We’d go so far as to categorize based on type (topographic, thematic for example) or scale (small, medium, multiscale) but the trend to create new brands and be seen as different is inevitable. A current fad is Map Stories or Story Maps. The idea that a map has a narrative and can tell a compelling story using a mixture of maps, graphics and textual components. As with most things, this idea isn’t new either. This map by the publishers Colortext was one of a series they labelled ‘Story Map’. It combines pictorial images, text and information that in this case tells the story of Scotland. It incorporates historical and cultural components in a place-based narrative.

It’s possibly the first of the genre of Story Maps. Ernest Dudley Chase also produced a number of his own maps in the mid-1900s that he titled Story Map too. This is a well composed Story Map or, as some of us might say, a map. It’s pictorial elements are well composed and the map has a good density of information. The decorative border of the tartans adds further interest and the map as a whole combines several integrated themes to tell the story of Scotland.

It’s possibly the first of the genre of Story Maps. Ernest Dudley Chase also produced a number of his own maps in the mid-1900s that he titled Story Map too. This is a well composed Story Map or, as some of us might say, a map. It’s pictorial elements are well composed and the map has a good density of information. The decorative border of the tartans adds further interest and the map as a whole combines several integrated themes to tell the story of Scotland.